- Program

- /

- Film Series

- /

- FIKTIONSBESCHEINIGUNG SPECIAL

- /

- Der Kampf um den heiligen Baum + A Lover & Killer Of Colour

Der Kampf um den heiligen Baum + A Lover & Killer Of Colour

Der Kampf um den Heiligen Baum

Wanjiru Kinyanjui, Germany 1995, 82 min, 35mm, English and Swahili with English subtitles

A Lover & Killer Of Colour

Wanjiru Kinyanjui, FRG 1988, 10 min, 16mm, Original English language version

Introduction by Karina Griffith

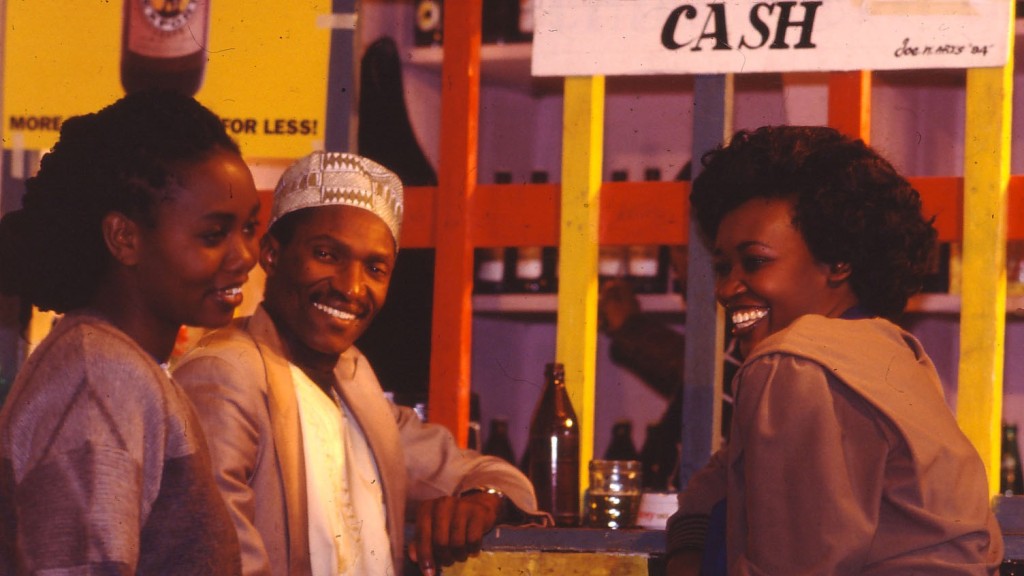

Watching Wanjiru Kinyanjui's Der Kampf um den heiligen Baum (The Battle of the Sacred Tree), you would never guess that this witty and assured feature was the director’s DFFB graduation project. Shot far from Berlin, on location in a Kenyan village with local actors, the film’s dialogue alternates between English and Kiswahili, with a soundtrack by the Senegalese musician Mamadou Mbaye. Based on a short story by the best-selling author Barbara Kimenye,the film follows Mumbi (Margaret Nyache), a young woman who leaves Nairobi and her abusive husband to return to her ancestral village. There she soon clashes with a Christian women's group, whose members are determined to eradicate every last trace of pre-colonial beliefs. They are particularly vexed by a magnificent tree, because the villagers believe it possesses supernatural powers. A cunning mayor and an amorous tailor leap to Mumbi's defense, but in the end it is ants that engineer what Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the doyen of Kenyan literature, once referred to as "Decolonising the Mind".

It’s midnight, and a young Black woman (Alida Babel) walks through Berlin on her own. Her heels click against the steps down to the U-Bahn, the train has just left, and the empty platform quickly morphs into a space of anxiety. Made during Wanjoru Kinyanjui’s studies, A Lover & Killer of Colour (1988) revolves around the anger unleashed by everyday experiences of sexist and racist harassment. What can be done with the aggression that builds in these moments of humiliation and powerlessness? Night scenes alternate with footage of the young woman’s studio as she paints and writes, a voiceover reading her furious words as she types: “If you do not stop / insulting me / you leeches / I will kill you / in this poem.” Wanjiru Kinyanjui’s directness rejects the sort of sublimation that may have kept this anger contained – even as the wish for reconciliation remains: “Through words, my trust is repaired / on white paper”. (KG)